Core Rules

The following works were influential in the creation of this hack:

- Blades in the Dark: Deep Cuts by John Harper

- Troika! by Melsonian Arts Council

- World of Dungeons by John Harper

- Troika! on the Borderlands by Chris P. Wolf

- Prime Material by Michael Hansen

- Shadowdark by Kelsey Dionne

- Errant by Kill Jester

- This Skeet by Rise Up Comus

This work is based on Blades in the Dark, product of One Seven Design, developed and authored by John Harper, and licensed for our use under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license. This work is an independent production by Emyrikol’s Games and is not affiliated with One Seven Design or the Melsonian Arts Council.

Table of Contents

- Character Creation

- Skills and Attributes

- Rolling the Dice

- The Spotlight

- Combat & Harm

- Magic

- Equipment

- The Dice of Fate

- Progress Clocks

- Enemies

- Notes for the GM

Character Creation

- Record your Stamina. It is 16.

- Record your Luck. It is 6.

- Record baseline possessions that every character starts with: 2d6 ivory pieces, a knife, 3 supply, 6 provisions.

- Choose or roll for a background.

- Choose or roll for a kind.

- Choose a name.

Character Advancement

When you make a roll using one of your Skills, put a mark next to it if you rolled below a 6.

When you have a chance to take a few days of downtime and reflect on your adventures, choose a Skill with a mark next to it and improve it by one level. If you were a novice, you become trained. If you were trained, you become an expert. Then clear all of your marks.

When you spend at least a week training a Skill, improve the skill by one level (or become a novice if you were untrained). This usually requires the assistance of a teacher, manual, spellbook, or similar. The GM has final say on what is sufficient to train you; the more skilled you become, the greater the requirements will be.

When you complete an adventure, you may improve one of your Attributes at the expense of another, if you wish. For example, you might shift your Grace up, but shift your Insight down in exchange.

Special Advancement

It is possible for your character to obtain new special abilities, similar to the ones that some backgrounds and kinds begin the game with. Special abilities are unique powers or capabilities that allow you to bend or break the basic rules of this game.

There’s no procedure for this kind of advancement; after character creation, special abilities can only be obtained through adventuring. You might learn secret combat techniques from a wandering mendicant; invent new magics or discover forgotten spells; receive a divine blessing from the deity whom you serve; or transform yourself through exposure to unstable sorcery.

You can find some examples of special abilities here.

Skills and Attributes

Every player character possesses five Attributes:

- Grace represents dexterity, precision, reflexes and overall finesse.

- Prowess represents strength, athletics, endurance and physical fitness.

- Resolve represents self-control, authority, willpower and composure.

- Cunning represents cleverness, trickery, subtlety, and powers of observation.

- Insight represents knowledge, wisdom, education and powers of deduction.

Each of these Attributes has a level that determines how capable you are in that area. When you start the game, two of them will be above average; two of them will be average; and one of them will be below average.

Your character also has various Skills, depending on which background you chose. For example, they might be skilled in Knife Fighting or Spells of Influence. Like Attributes, your Skills also have a level. You can either be a novice, trained, or an expert.

Rolling the Dice

The core of this game is a conversation. The players describe what their characters do, and the GM tells them what happens. If you attempt something trivial or impossible, the GM will simply describe the outcome. If there is an unavoidable cost that must be paid or a consequence that must be suffered, the GM will tell you what the price is.

When you face an avoidable consequence from a dangerous opponent or a challenging situation, the GM will describe the potential consequences (“if you attack, you might get hurt”). They will also tell you about the effectiveness or impact of your approach (“either way, you’ll inflict your weapon’s damage”). Then you roll the dice to see if you can avoid the consequences.

The “avoidable consequence” you’re rolling to avoid might be the threat of failure, if you’re attempting something particularly difficult or uncertain. It might be some straightforward unpleasantness, like suffering a physical injury or getting caught. It might be a complication, like alerting the guards or accidentally starting a fire. Sometimes, there will be multiple consequences that you’re rolling to avoid at once.

1. Choose an Attribute. Depending on your approach, one of the five Attributes will be most relevant to what you’re trying to do. If the Attribute is below average, you start with 0d; if it’s average, you start with 1d; if it’s above average, you start with 2d.

1. Choose a Skill. If you’re a novice, you don’t get any bonus dice. If you’re trained, add 1d. If you’re an expert, add 2d. If you don’t have any Skills that are relevant to your chosen approach, then this is an untrained roll.

2. Add dice for additional threats. If there’s more than one threat or consequence you’re rolling to avoid, add 1d for each additional threat. Feel free to suggest additional consequences to the GM for more dice! More consequences means more danger, but the extra dice mean you’re more likely to avoid any single threat.

3. Add bonus dice. You can add 1d if an ally assists you with a setup action, if some other advantage sets you up for success, or if you’re using masterwork gear.

4. Roll the dice. If you have 0d, roll two dice and pick the lowest result. Assign a die result to each consequence you’re facing.

Judge the results as follows:

- 6. You avoid the threat.

- 4-5. You suffer a partial or reduced consequence.

- 1-3. You suffer the consequence.

Resisting Consequences. If you wish, you can spend Luck to resist consequences. Each point of Luck you spend allows you to resist a single consequence. Usually, resisting means that the impact of the consequence is reduced by one step (i.e. from standard to limited). If it makes more sense, the GM also has the option to rule that your character completely avoids the consequence.

Critical Success. If you have any left over 6s at the end of the roll, you can spend them to increase the effectiveness of your action, to set up an ally, or for some other benefit or useful outcome agreed with the GM.

Risk and Effect Levels

Most the time, the GM can simply describe the potential consequences and impact of your actions in terms of the fiction. Sometimes, though, it’s helpful to have a more concrete way to talk about them.

Both consequences and effects are categorised into four levels: limited, standard, great and extreme. If you’re rolling against more than one threat, then each threat can have its own risk level. For example, the blaze that is slowly building behind you might only be a limited risk, but the skilled swordsman facing you down might pose a great risk.

If you are closely matched with an opponent or obstacle, then standard is the default for both. In most cases, you can take a bigger risk to achieve a greater effect - for example, by going all-in and fighting recklessly. When opponents aren’t closely matched, the more dangerous one gets more impact for less risk.

Untrained Rolls

If you’re a novice in a Skill, it doesn’t give you any bonus dice when you use it. If you’re completely untrained, it works the same way - you roll your Attribute without any bonus dice from your Skills. However, an untrained roll will usually be either more more risky or less effective than a trained roll, or else it will be made at desperate position. The GM has final say on whether a lack of training imposes this penalty to your roll.

Not everything can even be attempted without training. If you don’t know how to pick locks, then lockpicks won’t be useful to you no matter how graceful you are. If you don’t know magic, no amount of insightfulness will allow you to cast a spell.

Controlled Position

If you are in control and there’s no impending danger, there’s no need to make a roll. The GM simply describes what your character is able to accomplish without taking a risk or paying a cost.

Desperate Position

If you are outnumbered, outclassed, or attempting something very difficult, you might need to make a desperate roll to avoid the threat. A desperate roll is all-or-nothing: a 6 is a success, but a 5 or less means you suffer the full brunt of the consequences.

You can use desperate rolls to represent something like shooting a monster’s eye. It’s challenging and hard to pull off, but representing that difficulty in terms of increased risk or reduced effect doesn’t really make sense.

Setup Actions

A setup action is an ordinary roll where the intent is to assist another player. For example, you might create a distraction or protect the archer while they line up a shot. Assuming your roll is successful, choose one:

- The person you’re helping gets +1d to their own roll.

- The person you’re helping reduces their risk or increases their effect by one level (i.e. from limited to standard).

As usual, you only have to roll if there’s an avoidable consequence. If you can set up an ally without taking a risk, or simply by paying some cost, then you don’t have to roll.

Group Actions

When your characters work together to overcome some obstacle as a team, everyone rolls individually to see how their part of the consequences manifest. If you’re all trying to lift a gate together, for example, each member of the party would roll separately to see if they become tired from their exertions.

The benefit of a group action manifests in terms of risk and effect. When you combine your efforts, you’ll often have less risk or greater effect than you would have if you were tackling the problem individually. The same applies for NPCs joining a group action. They don’t roll, but their participation factors into your fictional positioning and informs the potential consequences.

More isn’t always better, though. If you’re trying to sneak through an enemy encampment, for example, a smaller group will be easier to conceal. Adding more people won’t make the task any easier - it might even increase the risk or introduce new consequences!

The Spotlight

This game doesn’t have rules for deciding who goes first. Instead, the spotlight shifts around from character to character. It flows with the conversation, always following the fiction.

It’s the GM’s job to manage the spotlight, shifting the focus around so that everyone (including non-player characters) gets a chance to do something interesting. As a player, you can also help out by handing the spotlight over to someone who hasn’t had a chance to contribute yet.

When the spotlight is on a player character, we’re asking them what they do. They’re the ones taking the initiative and propelling the fiction forward. Whether or not their action involves a roll, what happens next is in their hands.

When the spotlight is on something that threatens the player characters, like an enemy or a hazard, we’re asking how the player characters react. The GM tells the players what’s about to happen, and it’s up to them to decide how to respond.

Shifting the spotlight more aggressively is a great way to represent a more formidable threat. An enemy that seizes the initiative from the player characters, behaves unpredictably, and forces the players to react to its actions is going to be a lot more dynamic and challenging to deal with than a more passive threat.

Combat & Harm

Combat in this game works like any other action. When you engage an enemy in melee combat you will usually inflict your damage automatically, unless there’s a significant threat of failing to hurt the enemy at all. The main consequence that you’re rolling to avoid is whether they hurt you back.

Ranged combat is the same. If it’s a tricky shot, you might be rolling to see whether you miss. If you’re firing into combat, you might be rolling to avoid hitting one of your allies by accident. If it’s an easy shot, though, you inflict damage automatically.

Damage

After successfully harming someone, roll a d6 and consult the damage table for your weapon to see how much Stamina they lose. All modifiers to damage will, unless otherwise specified, modify the damage roll and not the actual damage inflicted. The damage roll can never be reduced below 1.

The damage roll is most commonly modified by the risk or effect of the action that caused it:

- If the damage is limited, apply a -2 penalty to the damage roll.

- If the damage is standard, roll damage normally.

- If the damage is great, apply a +2 bonus to the damage roll.

- If the damage is extreme, deal maximum damage automatically.

Damage rolls are a helpful procedure, not an iron rule. If it’s clear you’ve hurt someone but it’s not clear how much, use a damage roll to see how badly they fare. You don’t need to make a damage roll when the effects are obvious: if you slit someone’s throat or crush someone with a boulder, chances are they’re simply dead.

Dual Wielding. If you wield a weapon in each hand, roll the damage die for both of them and pick whichever result you prefer. If you’re wielding two different weapons, the larger weapon usually determines what Skill you roll to fight with them.

Range. If you need a way to divide up range increments, you can use the following scale: melee range, throwing range, bow range, extreme range. Assuming there are no obstacles to slow you down, it’s reasonable to move one of these increments in a short period of time (i.e. from throwing range to melee). If you are very fast or make a roll, you might be able to cover two in the same period.

Reach. Some melee weapons, like whips and polearms, have reach. Weapons like this give you an advantage (less risk or more effect) when engaging with an enemy that doesn’t have reach. Once they close into melee range, this advantage is lost.

Armour

There are four levels of protection that armour can grant. They are vaguely defined so that whatever assortment of protective equipment you’ve managed to cobble together can be assigned to an armour level. Armour works as a modifier to damage rolls whenever it makes sense for it to protect you from harm.

A target is considered to be Unarmoured (+1), Lightly Armoured (0), Modestly Armoured (-1), or Heavily Armoured (-2). Carrying a shield also reduces damage rolls by 1, on top of whatever armour you’re wearing.

Conditions

When something happens to weaken or impair you without inflicting damage, you suffer a condition. For example, you might complete a perilous climb but become Exhausted in the process. Or the bite of a venomous creature might leave you Poisoned. It might even be something more abstract, like a scathing insult that leaves you Humiliated.

In a situation where you’d reasonably expect a condition to hinder you, the GM may invoke it to do one of the following:

- Impose a -1d penalty to your roll.

- Increase the risk or reduce the effect of your roll.

- Introduce a new threat to your roll.

Conditions go away on their own after a little while, as soon as it makes sense in the fiction. If you’re exhausted, then resting will clear it. If you’re poisoned, then time or an antidote will be enough to cure you. If you’re humiliated, a strong drink or a good night’s sleep might help.

Serious Conditions. You can also use conditions to represent lingering wounds or deep traumas that hinder you more than simply losing Stamina would. A close brush with death might leave you Haunted, for example, or a devastating blow from a powerful monster might leave you with Broken Ribs. Clearing such conditions often requires an extended period of rest, the attentions of an expert healer, or powerful magic.

Healing

If you take a long rest of 8 hours or so and consume 1 provision, you regain 1d6 Stamina and 1 Luck. If you indulge yourself and consume 2 provisions, you regain 2d6 Stamina and 1d6 Luck.

A skilled healer can attempt to adminster first aid to an injured character; only one attempt can be made per injury. This restores 1d6 Stamina, at the risk of using up their healing supplies. If they don’t have the right equipment, they roll at the risk of making the injury worse. Various healing magic is also available in the form of potions and spells that can restore Stamina.

Death

If you fall to 0 Stamina, you are dying. You have about a minute, or enough time for your friends to make one attempt to heal you, before death comes for you. A successful attempt at first aid restores you to 1 Stamina.

When death comes for you, make a roll using your current Luck rating. On a 6, you are merely incapacitated, or saved by some bizarre twist of fate. On a 4-5, you’re left with a serious condition that serves as a debilitating reminder of your brush with death. On a 1-3, you die. If you have 0 Luck, you fail automatically and die.

Magic

Spells work like Skills. Every spell you know covers a category of magic, such as “Spells of Influence” or “Spells of Frost”. Check the glossary of spells for a more detailed description of the kinds of magic they cover, along with some example spells for each discipline.

Spells also have a Stamina cost, which must be paid to cast them whether or not the spell succeeds. The exact cost depends on the magnitude of magic you’re trying to work:

- 0 Stamina. Cantrips. Petty demonstrations of the craft. Weak force. Little hazard. Damage as Unarmed.

- 1-2 Stamina. Everyday magic. No more than a few minutes or throwing range. Moderate force. Minor hazard. Damage as Small Beast.

- 3-4 Stamina. Potent magic. No more than an hour or bow range. Strong force. Significant hazard. Damage as Modest Beast.

- 5-6 Stamina. Exhausting magic. Up to a few hours or extreme range. Serious force. Deadly hazard. Damage as Large Beast.

Magic is delicate and prone to failure when rushed. If you’re casting a spell in a controlled position, with plenty of time and no imminent threats, then you don’t have to make a roll. Otherwise, there’s always the risk that the spell fails, or misses the target, or is resisted by the target.

Spells are the work of a moment, but even the most taxing spells are limited in scope and duration. For more ambitious and powerful magical workings, you’ll need to turn to ritual magic.

Equipment

When adventurers prepare themselves for their next expedition, they may buy Supply for 1 ivory apiece. This might be something like a 10 foot pole, a coil of rope, a torch, a flask of oil, or even a spare quiver of ammunition. You don’t have to decide what it is when you buy it.

At any point during your adventure, you can expend a unit of Supply to produce a specific item of some kind. It can be anything you would expect a well-prepared adventurer to pack, but it can’t be anything rare and specialised - like a grappling hook or a healer’s kit. It also can’t be anything that costs more than 1 ivory piece.

Encumbrance

You may carry twelve things without issue. Some items are of inconsequential individual weight and only ever take up one slot, unless you have an awful lot of them. Provisions are 6 to a slot, supply is 1 to a slot, ammunition is 20 to a slot. For everything else, what constitutes a lot is up to your group to decide.

Large items are anything you need both hands to hold. They take up two slots in your inventory. Armour takes a number of slots equal to its protective value - 1 slot for light armour, 2 slots for modest armour, 3 slots for heavy armour.

If you find yourself carrying more than 12 items, you gain the Encumbered condition due to the inconvenient weight. The GM may invoke it whenever the weight of your equipment might hamper you.

Masterwork Gear

Masterwork equipment is rarer and more expensive than regular gear, but also more reliable and effective. Its exceptional qualities can provide assistance when they apply to an action, similar to a Setup Action.

When you get a piece of masterwork gear, make a note of what makes it special. A bow might be accurate at great distances, for example, or a shield might be resistant to fire. If the unique qualities of your masterwork equipment apply to a roll, you get +1d to that roll.

This bonus stacks with other sources of bonus dice, but you can only receive it from one piece of gear per roll. If you have multiple masterwork items that apply to a single roll, they don’t stack.

The Dice of Fate

When the GM isn’t sure how some situation should proceed, they can use the Dice of Fate to disclaim decision making and determine how things unfold. Turn to the Dice of Fate when you’re unsure of what should happen next and want to leave it up to the dice.

The Dice of Fate might be rolled to establish the weather, indicate a random NPC’s mood or attitude, or to determine the initial position when the player characters stumble across some uncertain situation.

If some Attribute/Skill or Tier rating is applicable, you can use that as a starting point for how many dice to roll. Otherwise, start from 1d for sheer dumb luck. Add 1d for every major advantage that applies, and subtract 1d for every major disadvantage.

Judge the results as follows:

- 66. No risk, exceptional fortune, an extraordinary outcome, or extreme impact.

- 6. Limited risk, good fortune, a desirable outcome, or full impact.

- 4-5. Standard risk, middling fortune, a mixed outcome, or partial impact.

- 1-3. Great risk, ill fortune, a poor outcome, or little impact.

The Event Roll

The Event Roll is a special use for the Dice of Fate which the GM can use to represent the passage of time, abstracting away the need for strict timekeeping or meticulous resource management. When the player characters are in a dangerous or uncertain area, the GM will make an Event Roll every so often. Once every hour or two is usually a good interval for a dungeon. For wilderness exploration over a longer period, every four hours may be more appropriate.

As usual, start with 1d for sheer dumb luck. Add 1d for each major advantage that makes exploration more expedient or safe, such as effective precautions or a useful spell. Subtract 1d for each major disadvantage that makes exploration more awkward or risky, such as encumbrance or poor visibility. As usual, a roll with 0d means that you roll two dice and pick the lowest result.

Judge the results as follows:

- 66. No event. Also, they discover some helpful hint or clue about a nearby monster, a secret feature of the area, etc.

- 6. No event. For now, the player characters can continue their exploration without interruption.

- 4-5. Impending event. Telegraph the approach of an event to the player characters. Skip the next roll and have it manifest instead.

- 1-3. An event manifests immediately.

Here are some generic event types that the GM can use when preparing a dangerous area or coming up with an event on the fly:

- Encounter. Roll for a random encounter and determine its reaction.

- Obstacle. Some kind of impediment or problem blocks the party’s progress.

- Exhaustion. Some or all of the party gain a condition such as tired, hungry or stressed.

- Depletion. Some resource is depleted. Torches burn out, rope is needed to proceed, etc.

- Locality. The weather changes, the environment shifts, a clock ticks up, or something happens nearby.

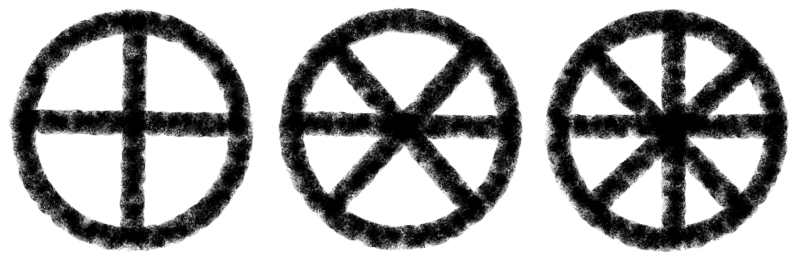

Progress Clocks

When an obstacle can’t be resolved by a single roll, you can use a progress clock - a circle divided up into segments - to track ongoing effort or the approach of impending trouble. The more complex the problem, the more segments in the clock.

As a general rule of thumb, each level of risk or effect is equivalent to one “tick” of the clock. Clocks should always reflect the fiction, though, not the other way around. Don’t be afraid to throw a half-filled clock away if the players come up with a clever plan to overcome an obstacle in one fell swoop.

You can also use progress clocks to represent long-term goals and projects that the player characters might wish to undertake, or to track ongoing background events and the passage of time. For example, you might use a clock to count down to the next Event Roll.

Enemies

The enemies that characters will encounter are not like them. As described in The Spotlight, the GM doesn’t roll attacks for enemies. Only the players generally roll the dice. When the spotlight is on your opponent, it just means that you’ll be rolling to avoid their attacks or react to their actions, rather than taking the initiative yourself.

For that reason, enemies only have four stats: Tier, Stamina, Armour and Damage.

Tier is a way to summarise the overall threat level of an enemy: how formidable, dangerous or skilled they are (especially in their element or area of expertise). It’s comparable to a player character’s Skill rating. If you’re rolling 2d and you’re fighting with a Tier 2 swordfighter, for example, you’re probably evenly matched. Although the GM will rarely roll an enemy’s Tier directly, they can use it as a rough guide when setting the stakes of a roll.

You can use the following list as a guideline when determining the Tier of an enemy or obstacle:

- Tier 0: A minimal threat. An unarmed civilian, a domestic animal, a mild hazard, a minor complication, a weak force.

- Tier 1-2: A standard threat. An armed soldier, a dangerous beast, a life-threatening hazard, a significant complication, a moderate force.

- Tier 3-4: A formidable threat. An elite adventurer, a deadly monster, an out-of-control hazard, a severe complication, a serious force.

- Tier 5-6: An extreme threat. An overwhelming opponent, a terrifying monstrosity, a natural disaster, an outright crisis, a devastating force.

Stamina, Armour and Damage work exactly the same for enemies as they do for players. Enemies can also have special abilities, just like player characters.

Player characters can’t increase their maximum Stamina without magic; most will never have more than 16 Stamina. Bear this in mind when creating enemies. You should use Tier to reflect an opponent’s overall threat level, rather than Stamina. An ordinary person has between 8 and 12 Stamina, so only give enemies more than this if they really are physically tougher than a normal person.

Multiple Enemies

When running a group of enemies, you don’t need to handle each opponent separately. Instead, you can treat the group itself as a single threat whose scale makes it more dangerous. You can represent their increased numbers by increasing the effective Tier of the enemy, by introducing multiple consequences that must be rolled against, or by applying some unavoidable cost.

For example, let’s say we have a warrior with Average Prowess and Trained Sword Fighting, giving them 2d. They’re fighting against some generic guards (Tier 1):

- Against a single guard, the warrior clearly outclasses them. They’ll gain some advantage such as reduced risk or increased effect.

- Against two or three guards, the GM decides to treat them as a single Tier 2 threat. The warrior is on even footing with them, with standard risk and effect.

- Against half a dozen guards, the GM decides to treat them as a single Tier 3 threat. Now the warrior is the one outclassed, contending with greater risk than usual.

- Against a dozen guards, the GM rules that it’s impossible to keep them all at bay. Unable to defend against everyone at once, the fighter suffers some unavoidable damage before rolling.

As usual, make your ruling based on the fiction and the tone you want for your game. Maybe you want to run a game where a single warrior can fend off a dozen guards at once? In that case, you might prefer to treat their attacks as two separate consequences. With double sixes, the warrior could come out of the clash unscathed.

Or maybe they’re not guards, but squabbling lowlives that trip over each other and are more interested in saving their own skins than scoring a blow? Their numbers might not give them any advantage at all! The only difference between a single foe and many is that the latter will take more time (and more rolls) to defeat or drive off.

Example Enemy

Silver Mimic

Tier 1

Stamina 10

Unarmoured (+1)

Damage as Weapon

An alchemical slurry that can imitate living shapes when threatened. They are clumsy and mindless, with silver eyes and jerky movements. They cannot speak, and only moan gutturally as they stumble at you with weapons that are plenty dangerous despite being fake.

Special: When weakened to half Stamina, the mimic collapses back into a pool of silver sludge. They cannot attack in this form and can only ooze slowly over the ground, but are difficult to harm - becoming Heavily Armoured (-2) against most ordinary attacks. Things like fire, frost and acid hurt them normally. They seek to merge with another injured mimic, allowing them to reform at full strength.

Notes for the GM

This is a game that blends the philosophy of so-called OSR/NSR games and Forged in the Dark games. At any given time, the players have two options at their disposal for dealing with a problem:

- Overcome the problem by expending resources, such as Stamina, Luck, Supply, or consumable items.

- Overcome the problem by engaging with the fiction, creatively using their Attributes and Skills to get the best risk and effect.

Sometimes, using up your precious resources to overcome an obstacle is the right call. If you can resolve an otherwise harrowing encounter by drinking an invisiblity potion and sneaking past, it may well be worth it. Often, though, it’s a failure state. Resources are limited and difficult to replenish, and the odds are often stacked against the player characters. After all, a normal person armed with a knife can wipe out half of a player character’s Stamina with a lucky roll.

In order to be successful adventurers, the player characters need to get creative. They won’t last long by trading Stamina with every enemy they come across, and their puny weapons won’t mean much when they’re contending with mighty and magical foes. But a well-planned ambush or a clever tactic with great effect can wipe out a powerful enemy in an instant - no damage roll required.

The progression system reflects this dynamic, as well. As your characters become more experienced and accomplished, they’ll gain new and improved Skills, Spells, and maybe even special abilities that allow them to bend or break the rules of the game. But their Stamina and Luck will never change, barring unusual circumstances. They never stop being ordinary people.

As the GM, your job is to hold up your end of this bargain. Be a fan of the player characters! They have no shortage of enemies; they don’t need the GM to be an adversary, too. If they come up with a clever plan to solve a problem, go with it! If it’s not quite right, try to say “no, but…” or ask the players to fill in the missing details, rather than simply shooting it down.

The player characters are fragile and human, but they can overcome overwhelming adversity if they are cunning and creative, and if they work together. Allow your players to earn their accomplishments and snatch victory from the jaws of peril, and you’ll end up with something that’s much more memorable than making attack rolls until the monster dies.

Perception

This game doesn’t have any “perception” or “awareness” skills. When it’s not clear to you whether a player character notices something or not, use the Landmark, Hidden, Secret system from DIY & Dragons:

- Landmark: If it’s obvious and you can’t miss it, then the player characters notice it immediately. No roll or cost is required.

- Hidden: If it’s not immediately obvious, then the player characters will notice it if they investigate. They may need to ask questions, interact with the environment, or pay some kind of cost (such as time spent searching) to find it. As long as they do so, it’s guaranteed that they’ll find it.

- Secret: If it’s obscure and locked away, there’s no guarantee the player characters will notice it at all. Even if you investigate, there’s no guarantee you’ll find it. You might need to ask just right the question, spend a limited resource or have access to a special skill, or make an uncertain roll to find it. Even if you do so, success is uncertain.

For example, consider three doors:

- Landmark: An ordinary wooden door. It’s one of the exits from this room. It’s impossible to look at this room and not know there’s a door there.

- Hidden: An entrance concealed behind a curtain. If you move the curtain, you’ll find it. If you spend some time searching, you’ll feel a draft.

- Secret: A magical secret door. If you can detect the presence of magic, you’ll sense an emanation from the bare stone. If you’re a skilled tracker, you might notice disturbances in the dust nearby. Most people will never know it’s there.

Knowledge

For player character knowledge, you can use a variation of the system described above called Common, Recalled, Obscure, suggested by Elmcat:

- Common: It’s something your character would expect to know based on their background, skills, or life experiences. The GM tells you the answer whenever you ask, restates it whenever you might have forgotten, and mentions it if it’s relevant.

- Recalled: It’s not something your character simply knows, but it’s something they know how to find out. They might simply need to think hard for a while. If they need to look it up or consult someone, they have an idea of where they need to go or who they need to talk to. If they pay the cost, they’re guaranteed to get the answer.

- Obscure: Your character doesn’t know and it’s not obvious how to find it out. This applies to knowledge that is rare, technical or secret. They might need to seek out an expert, but it’s not clear who. They might need to do their own research, or make a roll. Either way, there’s uncertainty and finding out the answer is not a guarantee.

If you make a roll for Recalled information, you’re rolling to see how much or how easily you can remember (not whether you know anything at all). If you make a roll for Obscure information, failure should never simply create a roadblock. Instead, you might get incomplete or partial information, multiple plausible answers, or a lead on where to go for a more reliable answer.

Consequences

Consequences can arise from unavoidable costs, or from avoidable risks that the players failed to avoid. A given circumstance might result in one or more consequences, depending on the situation. If you’re trying to pick a very complex lock, for example, it might take some time (an unavoidable cost) and also risk breaking your lockpicks (an avoidable risk).

The GM determines the potential consequences of the player characters’ actions, following from the fiction and the stakes, and describes them to the player before they try to do something.

Here’s a glossary of common consequences you might turn to:

- Less Effect. On a partial success, your impact is reduced by one step. On a failure, then perhaps future attempts will be less effective.

- More Risk. The situation you’re in becomes more dangerous and uncertain, meaning that your next roll will be even more risky.

- Complication. A narrative complication emerges. For example, something breaks or an opportunity is lost. The higher the risk, the more severe the complication.

- Progress Clock. This is the same as a complication, but more fine-grained. Mark 1 to 3 ticks on a progress clock, depending on the risk.

- Condition. You suffer some kind of ongoing impairment. The higher the risk, the more the condition will hinder you, or the harder it will be to clear.

- Harm. You suffer some kind of injury, reducing your Stamina. The higher the risk, the more damage you take (as described here).

Withdrawing. When a player makes a roll with limited risk, they usually have the option to withdraw and try a different approach instead of suffering a consequence. For example, on a roll of 1-3 they might choose to withdraw instead of trying again with more risk or less effect. On a roll of 4-5, they might choose to withdraw instead of succeeding and suffering a minor consequence.